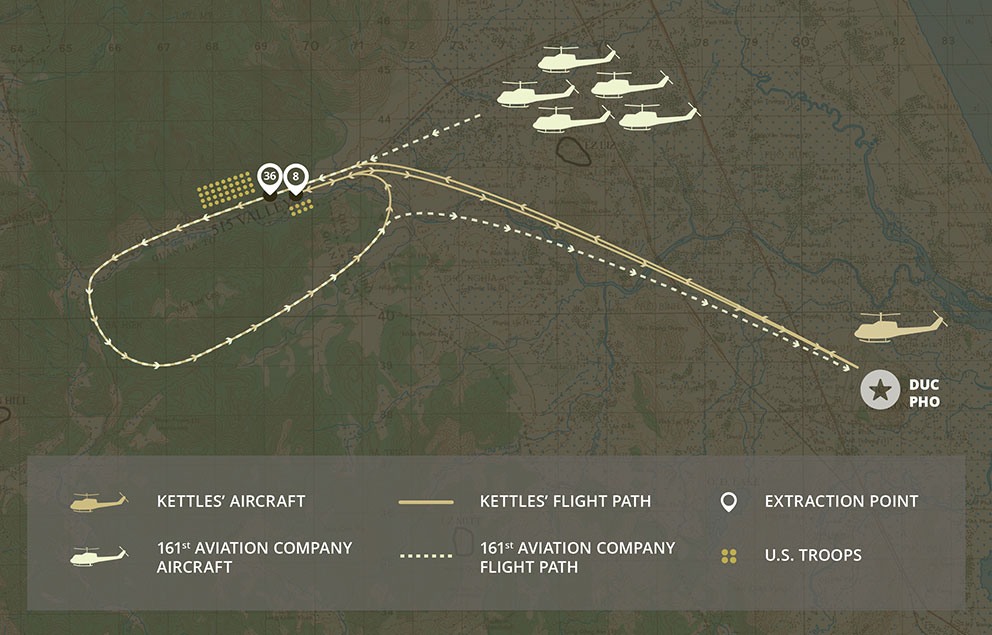

A TRUE AMERICAN HERO - LTC. (RET.) CHARLES S. KETTLES

|

| Art Work Courtesy Of The U.S. Army (Pentagon) |

Official Citation

The President of the United States of America, authorized by Act of Congress, March 3, 1863, has awarded in the name of Congress the Medal of Honor to Major Charles S. Kettles United States Army

For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty:

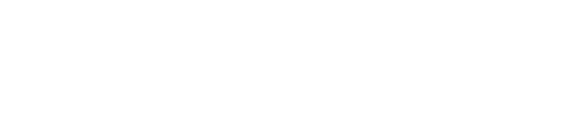

Major Charles S. Kettles distinguished himself by conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity while serving as Flight Commander, 176th Aviation Company (Airmobile) (Light), 14th Combat Aviation Battalion, Americal Division near Duc Pho, Republic of Vietnam. On 15 May 1967, Major Kettles, upon learning that an airborne infantry unit had suffered casualties during an intense firefight with the enemy, immediately volunteered to lead a flight of six UH-1D helicopters to carry reinforcements to the embattled force and to evacuate wounded personnel. Enemy small arms, automatic weapons, and mortar fire raked the landing zone, inflicting heavy damage to the helicopters; however, Major Kettles refused to depart until all helicopters were loaded to capacity. He then returned to the battlefield, with full knowledge of the intense enemy fire awaiting his arrival, to bring more reinforcements, landing in the midst of enemy mortar and automatic weapons fire that seriously wounded his gunner and severely damaged his aircraft. Upon departing, Major Kettles was advised by another helicopter crew that he had fuel streaming out of his aircraft. Despite the risk posed by the leaking fuel, he nursed the damaged aircraft back to base. Later that day, the Infantry Battalion Commander requested immediate, emergency extraction of the remaining 40 troops, including four members of Major Kettles’ unit who were stranded when their helicopter was destroyed by enemy fire. With only one flyable UH-1 helicopter remaining, Major Kettles volunteered to return to the deadly landing zone for a third time, leading a flight of six evacuation helicopters, five of which were from the 161st Aviation Company. During the extraction, Major Kettles was informed by the last helicopter that all personnel were onboard, and departed the landing zone accordingly. Army gunships supporting the evacuation also departed the area. Once airborne, Major Kettles was advised that eight troops had been unable to reach the evacuation helicopters due to the intense enemy fire. With complete disregard for his own safety, Major Kettles passed the lead to another helicopter and returned to the landing zone to rescue the remaining troops. Without gunship, artillery, or tactical aircraft support, the enemy concentrated all firepower on his lone aircraft, which was immediately damaged by a mortar round that shattered both front windshields and the chin bubble and was further raked by small arms and machine gun fire. Despite the intense enemy fire, Major Kettles maintained control of the aircraft and situation, allowing time for the remaining eight soldiers to board the aircraft. In spite of the severe damage to his helicopter, Major Kettles once more skillfully guided his heavily damaged aircraft to safety. Without his courageous actions and superior flying skills, the last group of soldiers and his crew would never have made it off the battlefield. Major Kettles' selfless acts of repeated valor and determination are in keeping with the highest traditions of military service and reflect great credit upon himself and the United States Army.

The Battle

May 15, 1967 | Duc Pho, Republic of Vietnam | Song Tra Cau riverbed

During the early morning hours of May 15, 1967, personnel of the 1st Brigade, 101st Airborne Division, were ambushed in the Song Tra Cau riverbed by an estimated battalion-sized force of the North Vietnamese army with numerous automatic weapons, machine guns, mortars and recoilless rifles. The enemy force fired from a fortified complex of deeply embedded tunnels and bunkers, and was shielded from suppressive fire. Upon learning that the 1st Brigade had suffered casualties during an intense firefight with the enemy, then-Maj. Charles S. Kettles, volunteered to lead a flight of six UH-1D helicopters to carry reinforcements to the embattled force and to evacuate wounded personnel. As the flight approached the landing zone, it came under heavy enemy attack. Deadly fire was received from multiple directions and Soldiers were hit and killed before they could leave the arriving lift helicopters.

Jets dropped napalm and bombs on the enemy machine guns on the ridges overlooking the landing zone, with minimal effect. Small arms and automatic weapons fire continued to rake the landing zone, inflicting heavy damage to the helicopters. However, Kettles refused to depart until all reinforcements and supplies were off-loaded and wounded personnel were loaded on the helicopters to capacity. Kettles led them out of the battle area and back to the staging area to pick up additional reinforcements.

Kettles then returned to the battlefield, with full knowledge of the intense enemy fire awaiting his arrival. Bringing reinforcements, he landed in the midst of enemy mortar and automatic weapons fire that seriously wounded his gunner and severely damaged his aircraft. Upon departing, Kettles was advised by another helicopter crew that he had fuel streaming out of his aircraft. Despite the risk posed by the leaking fuel, he nursed the damaged aircraft back to base.

EMERGENCY EXTRACTION

|

|

| Courtesy Of The U.S. Army (Pentagon) |

Later that day, the infantry battalion commander requested immediate, emergency extraction of the remaining 40 troops, and four members of Kettles’ unit who were stranded when their helicopter was destroyed by enemy fire. With only one flyable UH-1 helicopter remaining, Kettles volunteered to return to the deadly landing zone for a third time, leading a flight of six evacuation helicopters, five of which were from the 161st Aviation Company. During the extraction, Kettles was informed by the last helicopter that all personnel were onboard, and departed the landing zone accordingly. Army gunships supporting the evacuation also departed the area.

“We got the 44 out. None of those names appear on the wall in Washington. There's nothing more important than that.”

Retired Lt. Col. Charles Kettles

Once airborne, Kettles was advised that eight troops had been unable to reach the evacuation helicopters due to the intense enemy fire. With complete disregard for his own safety, Kettles passed the lead to another helicopter and returned to the landing zone to rescue the remaining troops. Without gunship, artillery, or tactical aircraft support, the enemy concentrated all firepower on his lone aircraft, which was immediately damaged by a mortar round that damaged the tail boom, the main rotor blade, shattered both front windshields and the chin bubble and was further raked by small arms and machine gun fire.

Despite the intense enemy fire, Kettles maintained control of the aircraft and situation, allowing time for the remaining eight Soldiers to board the aircraft. In spite of the severe damage to his helicopter, Kettles once more skillfully guided his heavily damaged aircraft to safety. Without his courageous actions and superior flying skills, the last group of Soldiers and his crew would never have made it off the battlefield.

WASHINGTON (Army News Service) -- The bullets came in fast and furious, a hail so thick it seemed like rain with a fog of green tracers. The men of the 176th Aviation Company were used to hot landings after months in the highlands of Vietnam, but this, this was something else.

A battalion's worth of fire -- small arms, mortars, grenades -- seemed to be trained on the Hueys all at once, clipping rotors, windshields, and fuel lines. Still, the pilots flew, their blades whirring and thunking as they approached the landing zone. They had been flying back and forth all day, bringing in fresh troops and ammunition, and taking out the wounded as the battle went from bad to worse. Forty-four Soldiers were on the ground, outnumbered, outgunned, and desperate.

It would take a hero -- several heroes, actually -- to rescue them, to get them home safe to their parents, wives, and children.

It would take daring, bravery, and guts. It would take someone like now-retired Lt. Col. Charles Kettles, who led the rescue -- and then went back again -- and will receive the Medal of Honor for it in a White House ceremony on Monday, July 18.

BORN TO FLY

Kettles was born to be a pilot. His Canadian-born father served in the British Royal Air Force during World War I and the U.S. Army Air Corps during World War II. He raised his son around planes, and Kettles grew up assuming "everyone would want to fly."

So when Kettles received a draft notice at the close of the Korean War, he was excited. It was an escape from two full-time jobs and an opportunity to "sleep in to as late as 6 in the morning." It was also a chance to fly.

He served in post-war Korea, Japan, and Thailand. He married and had children, one of whom would eventually fly for the Navy. He opened a Ford dealership back home in Michigan with his brother. Then he volunteered for Vietnam.

"The Army was in need of pilots," he explained. "They had spent a great deal training me. … I think we all have an obligation in this country to respond where the need may be. … It's your country. It's up to you to protect it."

VIETNAM

Then-Maj. Kettles deployed to Vietnam in early 1967 as a platoon leader and aircraft commander with the 176th, part of 14th Combat Aviation Battalion, Americal Division. "You questioned why anyone would be at war," he remembered. "They had so much territory that seemed to be unused. … It was an absolutely beautiful country."

Flying a helicopter was the best way to see it, too, added Kettles' gunner, Spc. Roland Scheck. Up a thousand feet or so, above the jungle canopy, the humidity decreased. Crews flew their helicopters with the doors removed, a weight-saving measure that also made for some free air conditioning.

|

|

Spc. Roland Scheck

(Photo courtesy of Roland Scheck) |

"It was wonderful, absolutely wonderful," said Scheck. "It was like a motorcycle in the sky, going 160 miles an hour. … It wasn't so gorgeous if you were down there working in one of those rice paddies, but if you flew over it, it was wonderful."

The war started for the company in earnest a few months later when it was assigned to support the 1st Battalion, 327th Infantry, 1st Brigade, 101st Airborne Division. The infantry unit always seemed to be in some sort of contact and it was the pilots' job to transport and supply them.

"Whenever we were told, 'tomorrow we're going to fly for the 101st,' all the gunners and crew chiefs said, 'Oh s---,'" said Scheck. It meant trouble was sure to follow.

Then-Sgt. Dewey Smith (right) was in the weapons platoon of B Company. His unit spent two, three, or even four weeks straight in the field.

|

|

Sgt. Dewey Smith

(Photo Courtesy of Dewey Smith) |

"Somebody in the brigade was continuously fighting each day, and if you weren't in contact, then somebody was stepping on a landmine," he said.

"They were always in action," said retired Lt. Col. Ronald Roy, then a pilot and warrant officer. Pilots typically flew 10 hours a day, although 16 or 17 hours wouldn't be unusual. "Being shot at or having an aircraft shot up was routine every day. That was one tough unit and if they were there, we were there. … It was like brothers taking care of each other."

By the second week of May, things got "pretty hairy," near Duc Pho in the highlands, said Smith. His platoon confronted more than 100 enemy soldiers on May 13. Another company was overrun the next day, while six other Soldiers found their reconnaissance patrol compromised. Kettles and another pilot managed to rescue them from a B52 bomb crater minutes before another bomb strike.

Kettles earned the Distinguished Flying Cross for his actions, an award that would be overshadowed by events the very next day, May 15.

CHUMP VALLEY

That's when the 176th inserted another reconnaissance patrol in a valley Soldiers nicknamed "'Chump Valley,' because someone said only a chump would go there," Kettles remembered. The men soon confronted a large enemy force, and Smith's weapons platoon and his company's 3rd platoon were called on as reinforcements.

The enemy "really opened up on us. It was just continuous," Smith said. The battle seemed hopeless from the beginning: 80 versus a battalion-sized force with only a small, shallow creek and a few trees and bushes between them. "I'm not going to say that I was afraid, but I was extremely apprehensive."

The battle raged for hours, and even heavy artillery and airstrikes couldn't dislodge the enemy, who would simply duck into bunkers and wait for the explosions to end.

|

|

Retired LTC. (then Warrant Officer) Ronald Roy (center),

Retired LTC, (then Captain) Donald Long (arms crossed).

Pilots Roy and Long were awarded the Silver Star.

The aircraft pictured was destroyed by mortar rounds while wounding

Long.

(Photo Courtesy of Ronald Roy) |

Pilots from the 176th made several trips, bringing in ammunition and reinforcements and evacuating the wounded. There was only one direction they could use to approach the landing zone, Roy recalled, and North Vietnamese forces poured hellfire on them in what he still believes was an ambush. It was certainly some of the most dangerous flying he ever saw in either of his tours in 'Nam.

"It was like rain … coming straight up out of the wood line," described Roy, (left) who earned a Silver Star. "Without hesitation, we flew through it. … We got shot at every day, and you'd lose a rotor blade or whatever, but never to this intensity."

"You saw those green tracers coming at you," said Scheck. "They looked like each of them was going to get you right between the eyes."

Two wounded Soldiers had dived into Kettles' helicopter just as a volley of bullets sprayed the aircraft, leaving about 30 rounds through the Huey. On their way back to Duc Pho they passed Roy and Long's Huey returning for their second rescue mission to Chump Valley. They radioed Kettles that he was leaking fuel. Kettles made it back to Duc Pho trailing fuel, but Scheck was wounded in the arm, chest, and leg, which ultimately lost above the knee. He would receive the Distinguished Flying Cross in addition to the Purple Heart. "I was the first guy whose life he saved," said Scheck.

The fire was so withering, Roy continued, "Soldiers couldn't even leave the limited safety of the trees to deliver the wounded to our helicopter, which touched down in the middle of the LZ. They would have been mowed down in seconds". He maneuvered his helicopter closer, but a mortar struck between the rotor blades, severely damaging the aircraft, and wounding Roy's copilot then-Capt. Donald Long in the leg and turning the four crewmembers into infantry Soldiers. Both pilots Roy and Long received the Silver Star and crew members Sp4 Hawley and Pfc Washington each received the Distinguished Flying Cross.

RESCUE MISSION

By late afternoon, the 176th Aviation Company was down to one working helicopter and 44 Soldiers who were fighting for their lives in Chump Valley. Scheck and Roy both remember hearing from multiple people that commanders ordered Kettles to stand down.

Kettles ignored them.

He coordinated with the 161st Aviation Company to obtain more helicopters and crews, scraping together six helicopters. It was another hot landing, but the gunships and the artillery provided enough suppressive fire for the Soldiers to board.

The last pilot in the formation confirmed they had all the Soldiers, and the helicopters took off. But he was wrong, dead wrong, someone from the command and control aircraft yelled over the radio. Eight Soldiers had been fighting a bit of a rearguard action and had been left behind.

NEAR DISASTER

From the ground, Smith watched the last helicopter take off: "If it's possible for your heart to fall into your boots, that's what mine did. I had three rounds left in my rifle. … My first thought was that I was going to have to start hauling boogy down the side of the creek and try to lose myself in the brush to start escape and evasion."

Horrified, Kettles turned his helicopter around. He only had one "ground pounder" aboard whereas the other Hueys were full. "You've got eight troops there," he explained. "I happened to be there, available, with the equipment to do it. If you left them for 10 minutes, 15 minutes, they would have been a statistic somewhere, either dead or prisoner of war."

The gunships were gone, the Air Force had been called off and the artillery was silent. Armed only with two machine guns, a couple of revolvers, a lot of nerve, and the element of surprise, Kettles "ratcheted up into a steep, left descending turn. It falls like a rock, and touched down."

Smith thought for sure the helicopter would either be shot down or be forced to turn around. The hail of machine-gun tracers and mortars was that intense, but Kettles never flinched, even when one "mortar round went off almost immediately off of the nose and took out part of each windshield and the chin bubble" and another damaged the tail.

"The emergency panel was still cold, no red lights," Kettles continued, joking that "the air-conditioning was good, with ventilation through the windshield and the chin bubbles."

The GIs sprinted to the helicopter "pretty dog-on fast," Smith remembered with relief. "All eight of us, we were hauling boogy. Nobody wasted any time. It was quick, seconds."

They were still under fire, and now they were at least 600 pounds overweight. The Huey fishtailed.

"I had to lower the collective to get my rotor (revolutions per minute) back up," said Kettles. "Leaving the nose of the skid on the ground, I put the RPM back up again. I'm trading that RPM for forward speed to put it in translation lift, which will give me clean air. If it's going to go, it will go at that point, or we're all 13 of us going to be infantry again.

"I didn't know whether we were going to get out of there, but I was going to give it my best try. After about five or six of those down the riverbed, it did fly -- like a two-and-a-half ton truck."

|

| A 176th Aviation Company UH-1D model Huey helicopter pictured in Vietnam, 1967. This was the helicopter normally flown by Maj. Charles Kettles, but it was undergoing maintenance, May 15, 1967, the day Kettles and his fellow pilots were called on to perform a dangerous rescue mission. |

AFTERMATH

When the men finally made it to safety, mechanics counted almost 40 holes in the aircraft. Smith was numb, so shell-shocked at first that he didn't even recognize a buddy. For his part, Kettles assumed, "That's just what war is. … We completed the thing to the best of our ability, and we didn't leave anyone out there. Let's go have dinner."

Much to his disgust, Kettles' commander moved him into flight operations, asking Kettles what they were supposed to do without any helicopters. (In reality, the company managed to get back in the air very quickly.) Then Kettles became the brigade aviation officer, but he didn't want to be behind a desk. He wanted to fly.

Kettles reluctantly accepted a Distinguished Service Cross for actions he didn't think were anything special and moved on with life. He returned to Vietnam two years later, commanding the 121st Assault Helicopter Company in the delta. He eventually found his childhood sweetheart again and got remarried. He retired from the Army, went back to school, and helped found the aviation management degree program at Eastern Michigan University.

And then a local historian, AVVA member Bill Vollano, came to interview Kettles for the Veterans History Project. He dragged the story out of Kettles. He wanted to know more. He thought Kettles deserved more than the nation's second-highest honor. He believed Kettles deserved the Medal of Honor, and he started contacting Kettles' old battle buddies for statements. He got Congress and the Army to reopen Kettles' file.

"He definitely deserves the Medal of Honor," said Smith, who left the Army as a staff sergeant decorated for valor after three consecutive tours in Vietnam. He noted his children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren have Kettles to thank for their lives too. "I really can't express how much respect I have for him. I'm sure it had to take a lot of courage. He might have been doing his job, but he did a hell of a good job."

Kettles, who credits the helicopter instead of his flying skills, prefer to see the medal as recognition for everyone who fought that May 15.

"The Medal of Honor is not mine alone," he said. "You've got 74 crewmembers out there. … It belongs to them as much as it belongs to me.

"The bottom line on the whole thing is simply that those 44 did get out of there and are not a statistic on The Wall in D.C. The rest of it is rather immaterial, frankly."

|

| Former Staff Sgt. Dewey Smith (left) poses with the pilot who saved his life in Vietnam, retired Lt. Col. Charles Kettles, in Ohio, May 2016. It was an emotional day for Smith -- the first time the two had met since May 15, 1967, the day Kettles turned his helicopter around to rescue Smith and seven other Soldiers who had been left on the ground during a dangerous extraction. |

|

||

|

Lt. Col. (Retired) Charles Kettles received the Medal of Honor 18 July 2016

US Army photo by Sgt. Brand

|

Frank Beckmann,WJR 760 interview with Lt. Col Kettles on April 18 (with permission)

Below are links to media outlets with articles. The two Mlive links are different articles

News Conference video at Michigan National Guard Office, Ypsilanti Michigan

USA Today Has a very good article on the events on May 15, 1967 rescue mission.

![]() A short video produced by the Ann Arbor VA Hospital about Chuck's mission.

A short video produced by the Ann Arbor VA Hospital about Chuck's mission.

All the information on this page was gathered from the Army's website pages in honor of Col. Kettles. Dogman